As you might have noticed, one of the key usability features that we were missing on Iconfinder was the ability to display so called “flash messages.” Flash messages are one-time notification messages shown to the user after processing a form or handling other types of user input, so the user knows if things went as expected. Changing your password without being told Your password was updated. can be a little confusing, so it was long overdue that we did something about something that obvious.

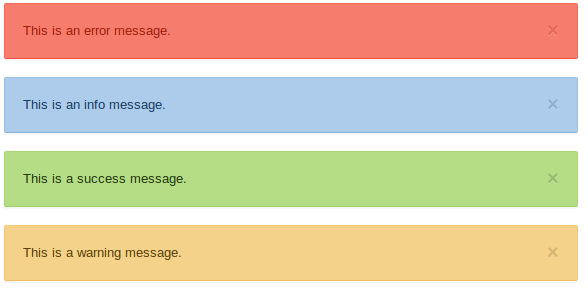

Example of flash messages.

Note: This is a cross-post of an article that I originally wrote on my company’s blog a while back.

Context is king

Most popular web frameworks already feature an easy drop-in way of showing these flash messages. Iconfinder is a heavy Django shop, and of course Django comes with its own messaging framework built in for just this purpose. But, like most other drop-in solutions, it rarely fits the bill of a larger site.

The built in messaging framework has a problem in that it’s not contextually bound - in other words, it’s not associated with any one form or page. This means, that messages from a specific form could under odd circumstances be shown in the completely wrong place, which is arguably more confusing than not being shown any message at all.

Furthermore, this also means that we can’t create “out of band” messages to be shown from asynchronous jobs, such as when we’re processing icon data, as that would just show up somewhere where the user might not expect it. What was left for us to do then, was to roll our own solution that would make it possible for us to do all the things we wanted.

Now, contextual is a pretty ambiguous term (which is why academics love using it) so we of course had to pick something more “tangible.” Django sites basically contain a bunch of views, which have the responsibility of displaying a specific kind of page, so as a starting place, we decided to bind messages to a specific view. As each user is also identified by a session, it made sense to start out with these two things defining the context.

Transient messages in Redis

Given the contextual nature of the messages, it is very likely that a user might have more than just one message waiting for him - especially if he or she is doing a lot of stuff at once. Therefore, the standard solution of using cookies to store the messages made no sense, as it would mean that a lot of pointless data was sent over the wire all the time. So, we have to store the data somewhere. Our primary PostgreSQL database is the first option, that comes to mind, but given that messages are shown once, that would mean that we’d be inserting and deleting a lot of data - something a relational database is usually not made for. Luckily, there are options out there that are basically made for this kind of workload, like for example our favorite key-value store, Redis.

Redis is essentially in-memory, but we do snapshots every minute and run a master/slave pair to make sure we don’t loose too much data in case of failure, but the loss of a couple of messages won’t be the end of the world, which makes it the perfect tool for the job.

The beauty of Redis is, that we can get away with a simple key structure: the base key is the application name, followed by the session key and finally by a view identifier. This makes insertion and retrieval of values very easy. The keys are also set to expire after a default period of inactivity, just to make sure we don’t have any orphaned messages lying around a week after you’ve changed your password.

messages:user-session-key:view-identifier

When a new message needs to be shown, we simply serialize it along with a bit of meta data and store it in a sorted set with the message’s timestamp as a score. This way the messages can be easily sorted by time or be purged using a garbage collection scheme if we run out of space.

The exposed API

One of the keys to keeping a large code base maintainable is to expose functionality through a stable, consistent API. The contextual messaging system adheres to this principle by exposing to simle methods: one to add a message and the other one to retrieve all the messages for a session in a view. If you’re a Pythonista, the following should look familiar to you:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | from messaging.models import Message Message.add(session_key = 'current-users-session-key', text = 'This *is* the message you are looking for.', title = 'Hello', status = Message.INFO, autoclose = True, view = my_view) messages = Message.get(session_key = 'current-users-session-key', view = my_view) |

A perfect case for a mixin

Django provides class based views which makes it easy to structure views and expose common functionality by harnessing inheritance and mixins. Because in most of the cases we would need to add and retrieve messages for the current view, to make it even easier we created a mixin that would provide some abstracted functionality to our view classes. The retrieval of messages for the current view is handled by the mixin so messages are ready to be consumed in the templates without having to call Message.get() in each view.

Adding a message is also a lot easier as we can figure out the view name and session from the view:

1 2 3 4 | class DashboardView(MessageViewMixin, TemplateView): def form_valid(self, form): self.add_message(text = 'Your settings have been changed successfully.', status = Message.SUCCESS) |

Doesn’t get much easier than that, huh?

Don’t be afraid to write code

If there is a functionality built into the framework that you need but it doesn’t fit you use case, don’t be afraid to write your own solution. In most cases you only need a minimum viable product that fits your needs really well rather than a full fledged library that can send a rocket to the moon.